Catalyst: Peter Booth

Concepts of proportion and size are skewed for the viewer as they are reduced to the scale of a minutiae creature, consumed by the totality of the dense jungle-scape.

Image credit: Peter Booth Painting (2022), 2022 oil on canvas 188.5 x 274.8 cm Courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane

It’s easier to see the darkness of things than it is to see the light. To borrow Joan Didion's syntax, I can remember now, with a clarity that makes the nerves in the back of my neck constrict, when this perception of darkness began, but I cannot lay my finger upon the moment light entered, cannot cut through the indistinctness and despondency to the exact place in the page where the scene is no longer as gloomy as it once was. 1

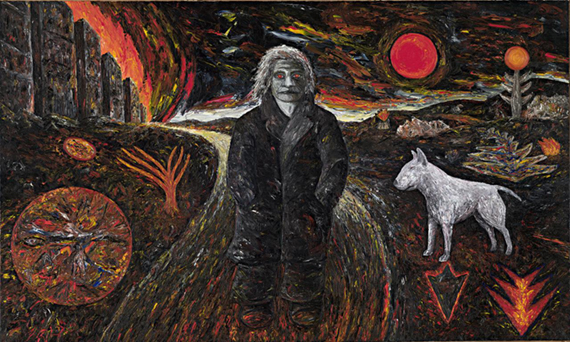

When I first saw a Peter Booth painting, I was 16 years old, and it was wintertime, and I walked into the senior art class in the upstairs corridor of the fourth floor wearing a school uniform which by that point in the year provided no warmth. Cold and fatigued, my peers and I gathered around to hear my teacher read, for the first time, her observations of a painting we were yet to see for ourselves. She read aloud something along the lines of, “a grey-haired man with red eyes stands on a winding path, in a black overcoat with oversized shoes and a white dog to his left-hand side. Surrounded by a flaming landscape, with a piercing orange sun, burning trees and an ashy sky, the figure stalls, staring neither back at you nor at the horizon, only at himself.” Off this observation, we were asked to draw an image and bring to life the rather sombre visual description we had just heard. When we eventually did see Peter Booth’s painting, with all its uncomfortable thalidomide associations, I could only think how obscure, how dismal, and how depressing an artwork like this was. Later in life, when I viewed the painting as an adult, it began to seem more jovial. It transformed from being a prophesy of doom to a fantastical figment of the imagination; a vision from an Australian artist who sees the world not only for what it is but what it could become.

The artwork, simply titled Painting (1977), gifted to the National Gallery of Victoria in 1978, has come to represent a synergy of Booth’s artistic inclinations and painterly sensibility. So too has his work Painting 1978 (1978), which merges the artist’s interest in figuration, the angular forms of which his 1960s hard-edge paintings are known, with his fascination with the landscape, and the rather sinister quality that shadows his overall oeuvre. This oeuvre, which resists easy interpretation, is comprised of paintings and drawings that equally allude to psychic states of disturb as they do idyllic spaces of arcadia. His most recent landscapes, painted between 2020 and 2022 capture this dichotomy. On view in TarraWarra Museum of Art’s current retrospective, Painting (2022) depicts nature in its most sublime and wild form. In this Jumanjian-like panorama, a biomorphically sized blue bug is seen peering between overgrown vines and saplings. Concepts of proportion and size are skewed for the viewer as they are reduced to the scale of a minutiae creature, consumed by the totality of the dense jungle-scape. Isolated and withdrawn, the viewer is left unprotected from the forces of nature and the folly of human endeavour.

Unlike Booth’s earlier works, there is no obvious darkness to be seen here. The womb-like colours and surrealist tones are no longer present. Instead, there is pure light: light of the sun, light of potential exploration, light of new beginnings. Here, the viewer has woken up from what Rosalie Gascoigne termed “the nightmare of isolation, darkness and urban loneliness.” They have woken to evidence of Booth’s love of the bizarre and the dramatic, his all-encompassing attraction to the world and all its glory. They have woken to all the light he has to give.

1. This paragraph is a re-phrasing of the opening to Joan Didion’s famous essay ‘Goodbye to All That’ in Slouching Towards Bethlehem (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1968), 225-26.

Image credit: Peter Booth Painting (1977), 1977, oil on canvas 182.5 × 304.0 cm, Courtesy the artist and National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Image credit: Peter Booth Painting (1978), 1978, oil on canvas 198 × 275 cm, Courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 41 (Feb – Apr).

Click here to Subscribe