David Goldblatt: Review

The photography of David Goldblatt has the rare capacity to expand our understanding of place and time.

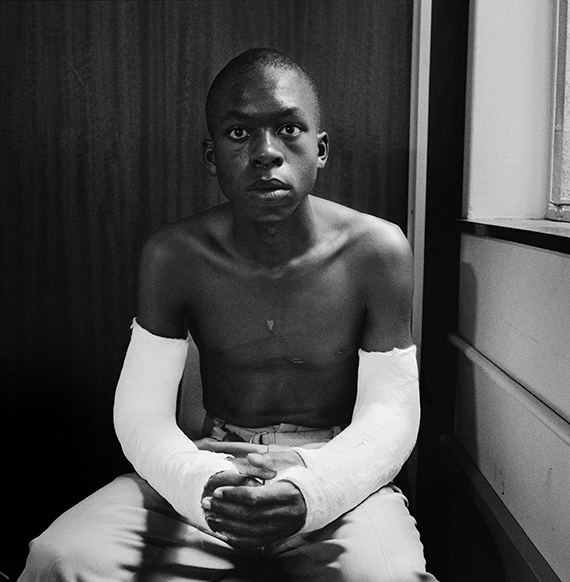

Image credit: David Goldblatt, Fifteen-year old Lawrence Matjee after his assault and detention by the Security Police, Khotso House, de Villiers Street, 1985, silver gelatin photographs on fibre-based paper. Courtesy the artist, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town and Pace/MacGill, New York © the artist

Images by David Goldblatt communicate directly and with humility, bearing witness to some of the most insidious and diabolical years of recent human history. His career is represented in the forthcoming exhibition, David Goldblatt: Photographs 1948–2018 as part of this year’s Sydney International Art Series at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney.

Born in 1930 in the Johannesburg gold-mining suburb of Randfontein, Goldblatt was a fledgling photographer of 18 when South African apartheid was institutionalised in 1948. And for six decades, until his death in June this year, he tasked himself with the role of documentarian and witness to the circumstances that surrounded and enabled racial segregation and political and social discrimination. “Apartheid became very much the central area of my work, but my real preoccupation was with our values … how did we get to be the way we are?”

Unlike a journalistic photographer, who might seek to represent the moment of heat – the news story, the action – Goldblatt took a less spectacular, more humanistic approach with his photo essays. In his extended engagement with the South African situation, he took long, slow looks at his compatriots. He made portraits of the people and places, and allowed his subjects space and context by photographing them in the peripheries of drama, the circumstances that led to violence, or the situation afterwards.

In an image from 1985, for instance, a teenager looks just past the frame that Goldblatt has placed around him. His arms form a second frame. They are encased in white plaster and clasped between his knees. In a formal reading of this composition, these arms draw our eyes around the image and back to the boy’s face, over and over. Though he looks calm, his face registers both alarm and exhaustion; urgency behind a veil of fear. The title of this work is Fifteen-year-old Lawrence Matjee after his assault and detention by the Security Police, Khotso House, de Villiers Street, Soweto, Johannesburg (1985). In the years before apartheid was dismantled in 1994, and before Nelson Mandela ascended from being a political prisoner to the first black president of South Africa in the first election to allow black people the vote, violence was, of course, commonplace. Matjee’s plaster-cast arms are the result of a police arrest, during which he was dragged by his feet from his home, his arms dislocated in the process.

Text is significant to Goldblatt’s work. Although the photographs are intensely communicative, they are made more potent, more open by explication in their captions. This sense of voice and context being bestowed on these images is perhaps most keenly felt in the 2008 series Ex Offenders at the Scene of Crime. For these images, Goldblatt worked with criminal offenders and alleged offenders, photographing them at the scene of the crime or arrest, each portrait accompanied by the subject’s own account of what happened. Often, this is the first record made outside of the judicial system, and therefore the first received without judgement.

This type of documentary image-making is sometimes referred to as ‘aftermath photography’, implying some distance from the vitriol, action or drama of the events central to the photograph. Perhaps it’s worth noting that although Goldblatt doesn’t showcase the drama, he was such a constant resident within the events and the heartbreak of apartheid that his work remains embedded in it, as though simply stilled – like taking breath or offering a pause – rather than being removed from the spectacle. A miraculously significant series included in the forthcoming exhibition, curated by Rachel Kent, is In Boksburg, a body of work that deftly gives shape to the mundane patterns of life during apartheid and the routine dynamics that made the racist regime possible.

Initially commissioned by Optima magazine in 1979, In Boksburg was rejected by the publication but taken up by German publisher Steidl in 1982. The photo essay shows the interwoven but segregated lives of black and white South Africans in the suburb of Boksburg: a legally white-only town on the eastern periphery of Johannesburg that was heavily dependent on black labour. In these images, white families go about their undramatic lives. They take ballet lessons. They sit on midcentury settees, within clean-lined architectural spaces. They mow their precise lawns. In the same town, black labourers work concrete mixers to build the clean-lined architecture. They do their shopping. They wait for buses and work in shops. The lives of these two groups intertwine, but seldom meet. The effect is unsettling.

“Boksburg was shaped by white dreams and proprieties. Most pursued the family, social and civic concerns of respectable burghers anywhere, some with compassion, yet all drawn into a fixity of self-elected, legislated whiteness,” as Goldblatt stated in the publication’s foreword in 1982. “Blacks were not of this town. They served it, traded with it, received charity from it, and were ruled, rewarded and punished by its precepts. Some, on occasion, were its privileged guests.”

This all calls to mind Hannah Arendt’s well-worn phrase about the banality of evil: these Boksburg lives appear, as Arendt had put it some years earlier, “terrifyingly normal”. Goldblatt’s photographs offer humanity on both sides of the equation: a picture of normal lives within an abhorrent system. “I was asking myself how it was possible to be so apparently normal, moral, upright – which almost all those citizens were – in such an appallingly abnormal, immoral, bizarre situation.” Goldblatt noted in conversation with Paul Weinberg. “I hoped we would see ourselves revealed by a mirror held up to ourselves.”

Goldblatt observes the architecture of apartheid with keenness, bearing witness to it and offering it up through his miraculous, empathetic lens, and he achieves this access and comment without anger. “I didn’t regard the camera as a weapon in the liberation struggle,” he said; rather, his work and his tools became a point of three-way discussion “between myself and whatever I photographed and my compatriots”. This discussion might just expand a viewer’s experience of a place and time: surprising in its beauty, difficult in its clear-sightedness and generous in its allowance of dignity.

David Goldblatt: Photographs 1948–2018 was part of the 2019 International Art Series at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney.

David Goldblatt: Strange Instrument, curated by Zanele Muholi is on show at Pace, New York, in collaboration with Yancey Richardson Gallery until March 27, 2021.

David Goldblatt is represented by Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

mca.com.au

pacegallery.com

davidgoldblatt.com

goodman-gallery.com

Image credit: David Goldblatt, A plot-holder, his wife and their eldest son at lunch, Wheatlands, Randfontein, 1962, silver gelatin photographs on fibre-based paper. Courtesy the artist, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town and Pace/MacGill, New York © the artistt

Image credit: David Goldblatt, Hold-up in Hillbrow, Johannesburg,1963. Courtesy the artist, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town and Pace/MacGill, New York © the artist

Image credit: David Goldblatt, Blitz Maaneveld at the Terrace, Woodstock, Cape Town, where he murdered a man with whom he had been gambling. 7 October 2008, 2008, silver gelatin photographs on fibre-based paper. Courtesy the artist, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town and Pace/MacGill, New York © the artist

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 24 (Nov 2018 – Jan 2019). Click here to Subscribe