Plastic Forms: Michelle Ussher

Is there a feminine creative form, and if so, what does it look and sound like? VAULT explores the art and enquiry of Michelle Ussher.

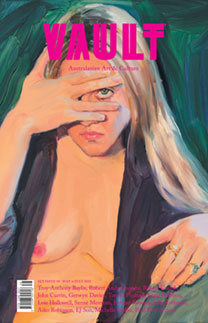

Image credit: Michelle Ussher, Medusa beheads herself (For Artemisia), 2017, oil on linen, 122 x 92 cm. Courtesy STATION

I settle into a Zoom call with Michelle Ussher; it is early morning in England where Michelle is based and she is yet to have her morning coffee. Michelle has just completed a thesis on aesthetics and our conversation veers between serious philosophical concerns and Michelle’s artistic practice, peppered throughout with her lively laughter and humour.

Ussher’s career started in Melbourne in the mid-2000s. She graduated with a degree in painting from RMIT, followed by an honours degree in drawing from VCA after which she moved to the United Kingdom. In 2020 she completed her Master of Arts in Aesthetics at Kingston University London where she was supervised and influenced by the work of Catherine Malabou – a prominent philosopher and protégé of Jacques Derrida.

Ussher’s work spans painting, ceramics, sound, performance and writing – both creative and theoretical. Tired of hearing about the masculine methodology for building a career as an artist – such cliches as ‘go big’ or ‘choose your thing and then repeat it’ – she began considering how female artists work, how they sustain their careers and how their careers evolve vastly disparate to those of their male counterparts. This eventually led Ussher to her desire to articulate a feminine creative form.

Central to Ussher’s concept of a feminine creative form, and her art practice more broadly, is the concept of plasticity. Drawing on the work of Catherine Malabou, who has passionately argued for the connection between philosophy and neuroscience through her interpretation of plasticity, Ussher speaks about plasticity as a concept with change at its core. She defines plasticity as “the taking and giving of form.” In our recent discussion, she used the example of clay, its malleable and transformational nature, to illustrate this idea of change. There is a giving and receiving within plasticity, an exchange, that flows in both directions. Ussher points out that plasticity differs from elasticity in that plasticity is permanent, it doesn’t go back to its previous shape, and thus there is a destructiveness inherent too, a permanent change that impacts and shapes us.

Ussher posits that plasticity embodies the feminine creative form – unfixed, experimental and changing over time. A form that moves inside out, upside down and detours to bring itself into being. I think it is important to point out here that Ussher says she doesn’t intend to gender creativity as male or female. Rather, she is talking about the masculine and feminine constructs within our society; she believes that both constructs can and do include the spectrum of gender.

Ussher’s boredom with historic and contemporary portrayals of women in myths and popular culture – for example, the prevalence of films centering around a woman’s murder or historic myths about female betrayal – has moved her to create bodies of work that reconceptualise and unpick these narratives. Is it your body I hold in my arms or the sea? (2016) takes the enduring metaphor of ‘woman as water’ – along with Jonathon Glazer’s 2013 film Under the Skin, starring Scarlett Johansson – as an inception point. In the film Johansson is an alien who comes to earth and preys on men in Scotland, consuming them with her alien body fluid. This misogynistic and limiting portrayal of Johansson’s character, and the recurring cliché of woman as water, coalesced with a research trip to Athens and Ussher’s interest in Lekythoi vases, beautiful burial vases that use a white ground technique and feature humorous cartoons drawn by friends of the deceased.

Painting forms an important part of Ussher’s creative output, accompanying changes and developments throughout her career and her movement into other mediums. Using oil paint primarily, her work sits between figuration and abstraction. She draws on colour palettes from historic paintings by famous male artists, creating works that encompass this history but represent new narratives and entanglements with her own imagination.

Ussher’s painting process itself is plastic. She sands back areas of the painting, proudly covers mistakes and allows the work itself to lead her as she creates it. Ussher is interested in the aesthetic of decay and the weathered patina created by the passage of time, elements of which are visible in the sanded back and scumbled surfaces of her paintings. The action of sanding the painting back also connects with her interest in revising and changing historic narratives. In doing so, she works with processes drawn from automatic drawing and frottage (taking rubbings of a texture through a sheet of paper) used by spiritualist painters in the past. Some of these processes are visible in the vibrant series Two Eyeballs on the Run – Looking for a New Head to House from 2012, otherworldly works in ghostly layers of golds, pinks, yellows.

A more recent body of work is Medusa’s Room (2017), developed during a residency at the British School at Rome. Reading Julia Kristeva’s book The Severed Head (2012) led Ussher to research the myth of Medusa. After exploring the Roman version of the myth, Ussher shifted her enquiry to the perspective of Medusa herself, considering how Medusa can never look at anyone she loves without turning them to stone. In the series, Ussher also explores ideas around women’s pleasure and male fear, and representations of female pleasure in heterosexual pornography. In the powerful red painting Medusa beheads herself (For Artemisia) (2017), we see Medusa’s head surrounded by boobs rather than the traditional snakes she is often pictured with, Ussher suggesting that only Medusa would be able to behead herself.

In a series of ceramic works from 2017–18, which includes Tutti Fruity (2018) and Saggy Boob Vase (2017), Ussher explores the female body and the breast/boob dichotomy. When we talk over Zoom, she jokes about having wanted to write about Freud and the boob at the time of making these works. The layered boob-shapes that make up the vases’ construction manifest the voluminous nature of a breast filled with milk in a lighthearted and humorous way; when exhibited, these vases hold flower arrangements. Ussher is interested in the difference between what the boob represents for a woman, in the context of feeding a child, and what the breast is in our society – a symbol of female sexuality and pleasure.

Ussher will be exhibiting in mid-2022 at Sydney’s STATION, her first solo exhibition in Australia for a couple of years. For the show Ussher is excited to be presenting a series of ceramic works born out of residencies at the British School at Rome and West Dean College of Arts, where she now works. West Dean College is located in rural England, established by the American art patron and poet Edward James in 1971 – it is known for holding a remarkable collection of surrealist artworks.

Inspired by the sketchbooks and letters of these surrealist artists, including Leonora Carrington, Ussher draws on ideas of hybridity and changing form in this series of ceramic instruments. Riffing off the ocarina, these adapted instruments feature metallic glazes and when Ussher plays some of them for me they make fun, unexpected sounds. Here, Ussher has returned to the idea of ‘woman as vessel’, unpicking this persistent and reductive metaphor with a dose of humour.

Working across painting, ceramics, sound and performance, Ussher’s evolving and ever-changing practice takes many of the clichés about women that persist in our society – women’s laughter, the boob, woman as water, the body as vessel, female betrayal – head-on. She explores these ideas in unexpected, interesting and beautiful ways, all the while recontextualising historic narratives, shifting our perspective and rebuffing clichés.

Michelle Ussher will have a solo exhibition at STATION, Sydney from June 18 to July 23, 2022.

Michelle Ussher is represented by STATION, Melbourne and Sydney.

stationgallery.com.au

Image credit: Michelle Ussher, Tutti Fruity, 2018, glazed porcelain oil paint and beeswax 45 x 45 x 25 cm.Courtesy STATION

Image credit: Michelle Ussher, TarraWarra Biennial 2018: From Will to Form, 2018, Tarrawarra Museum of Art, Healesville. Photo: Andrew Curtis. Courtesy STATION

Image credit: Michelle Ussher, TarraWarra Biennial 2018: From Will to Form, 2018, Tarrawarra Museum of Art, Healesville. Photo: Andrew Curtis. Courtesy STATION

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 38 (May – Jul).

Click here to Subscribe