Helmut Newton’s World of Women

HELMUT NEWTON: In Focus at the Jewish Museum of Australia explores the photographic output of arch provocateur Helmut Newton. VAULT takes a deeper look at the exhibition.

Image credit: Helmut Newton, Woman Into Man, Paris, 1979, Copyright Helmut Newton Estate, Courtesy Helmut Newton Foundation

With an output as recognisable as it was controversial, Helmut Newton (1920–2004) described himself as “a professional voyeur.” He had little time for some of his more pretentious colleagues, and often reiterated the mantra that “there are two dirty words in photography: ‘art’ and ‘good taste’.”

HELMUT NEWTON: In Focus (until January 29, 2023), curated by Eleni Papavasileiou and Cathy Pryor, traces the early life of Helmut Neustädter. His mother Klara came from a wealthy German Jewish family, and had been widowed young. Newton was the only child of her second marriage to Max, and the family lived a bourgeoisie existence in Berlin. Newton became attuned to the erotic possibilities of photography as a child after discovering his older half-brother’s stash of ‘girlie magazines’ in the locked drawer of a writing desk. Newton was particularly taken with the monthly Das Magazin and its selection of naked models in boudoir poses. “I would jimmy the drawer, then take the magazines into the loo and lock myself in, to study them very closely ... I was spending a lot of time in there. Eventually, my mother became concerned that I was constipated,” he related in his 2003 autobiography. In 1932 Newton bought his first camera, an Agfa Tengor Box.

Inspired by the works of Hungarian French photographer Brassaï (Gyula Halász, 1899–1984) and photojournalist Dr Erich Salomon (1866–1944), the original ‘candid camera’ photographer, Newton left school at the age of 16 to pursue his vocation. Somewhat prophetically, his father remarked, “My boy, you’ll end up in the gutter. All you think about is girls and photos.” In 1936, Newton was hired as an apprentice to the famous photographer known as Yva (Else Ernestine Neuländer-Simon, 1900–44), who perished at Majdanek concentration camp. Yva had a profound effect on Newton. “I worshipped the ground she walked on,” he would later confide. “I have always done my utmost to keep her memory alive. She was a great photographer and an exciting woman.”

After the Nuremberg Laws were enacted in 1935, life for the once-prosperous Neustädter family deteriorated. After Kristallnacht in 1938, Newton’s parents made plans for him to leave Germany, travelling via train to Trieste then via boat to Singapore. From Singapore Newton travelled to Melbourne and it was there, on December 4, 1946, that Helmut Neustädter changed his name to Helmut Newton. Opening a small studio in Flinders Lane the same year, he met and later married June Browne (1923–2021), a local actress and photographer who later went by the stage name of ‘Alice Springs’. Newton spent a decade in Melbourne establishing his career with a mixture of commercial, editorial, fashion and portrait work. He would maintain this varied practice when he left Australia for London in 1957.

On loan from the Helmut Newton Foundation for the exhibition at the Jewish Museum are works from Newton’s Private Property portfolio (1972–83), 45 images originally published in 1989. Newton preferred to shoot on-site with natural or available light and minimal equipment. “I have always avoided photographing in the studio. A woman does not spend her life sitting or standing in front of a seamless white paper background,” he observed. “Although it makes my life more complicated, I prefer to take my camera out into the street, into public and private spaces, places often inaccessible to anyone but the rich. And places that are out of bounds for photographers have always had a special attraction for me.”

Newton had an abiding love of hotels, stemming from his childhood. For Newton, hotels were luxurious and transgressive spaces, where fantasy lingered behind every door. The infamous Saddle I (1976), of a model in jodhpurs and boots kneeling on a bed wearing a saddle on her back, was for Vogue, featuring Hermès. Newton decided to represent the boutique, “as the most expensive and luxurious sex shop in the world. In its glass cases there were displayed great collections of spurs, whips, leather ware and saddles.” Other works, from Viviane F., Hotel Volney (1972) to Woman Into Man (1979), showcase Newton’s fetish with hotels as spaces charged with decadent abandon.

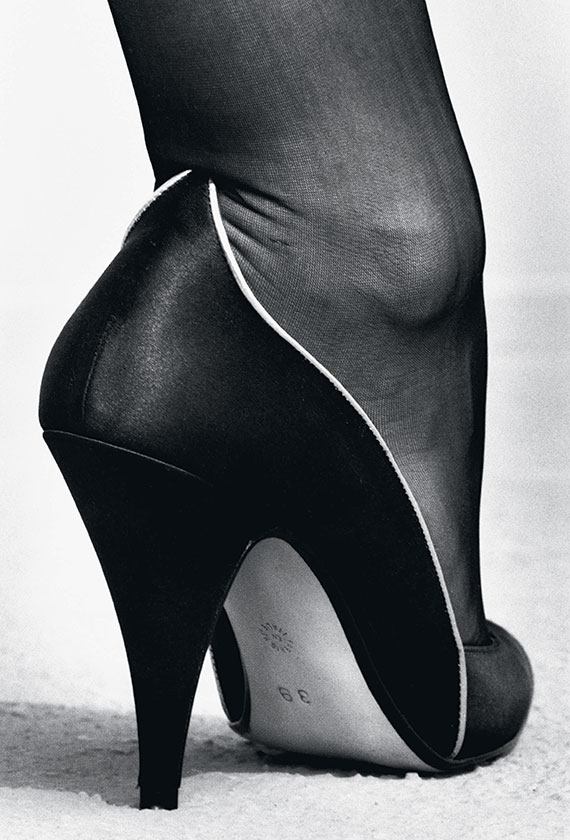

By 1961, Newton and his wife had settled in Paris where he established an international reputation at French Vogue. His fashion campaign work for the likes of Yves Saint Laurent (1982–95), Chanel (1983-84) and Thierry Mugler (1998–99) was unconventional. Although precise, Newton’s works suggested a spontaneity and physicality that made other advertising seem wan, conventional and dated. At the same time, Newton’s striking, often libidinous, images of women have been variously described as perverse, sexist and misogynist. Vertiginous heels, stocking tops, ankle chains, bondage wear and a paucity of clothing characterise his more risqué output. Indeed, the term ‘porno chic’ was coined in connection with his first survey book, White Women (1976).

Certainly, Newton delighted in challenging prevailing stereotypes around female power and desire, but he shrugged off the criticism of his uncompromising aesthetic by declaring: “My women always come out on top.” Indeed, there is an almost operatic, or heroic, quality to Newton’s female subjects. His nudes are strident, unapologetic, dominant. One of Newton’s more frequent subjects, French actress Catherine Deneuve commented, “One is always hoping that the picture will give an answer to the question that one is putting to it. Helmut’s photos are ‘revealing’, yes, but they are also always mysterious. One always wants to know more, but they only give part of the answer. That’s why women like him so much.” These highly stylised images look like fragments from a longer narrative, a cinematic disclosure that is never resolved, and is all the more resonant for it.

Actress Charlotte Rampling worked with Newton quite early in her career, including a famous nude session in 1973 at the Hôtel Nord-Pinus in Arles when she was filming Caravan to Vaccarès (1974). The images that subsequently appeared in Vogue, including one of her seated on a heavy wooden table wearing nothing but sling-backs, led the publication to declare her “the sexiest woman in the world.” Speaking of photo shoots, Newton admitted, “My attention seems to flag after the second day, and I get bored. I put this down to my superficial nature. This is why I could never do movies: to give a month, maybe a year to one project seems impossible to me.” And yet it was precisely this filmic quality in Newton’s approach that Rampling responded to. “If you look over the different works of Helmut, they’re so varied, each one is telling a story. He’s sort of a still movie director, and that’s what he’s always tried to create, he’s always put his subject in a décor that speaks.”

In 1980, Newton commenced his Big Nudes series, inspired by full-length police identity photographs of German terrorists like the Baader-Meinhof Gang. It was appropriate that Big Nude III (1980), of a resplendent Henriette Allais, was chosen for the cover of one of the most grandiose and landmark events in publishing history. Newton’s collaboration with his friend, the German publisher Benedikt Taschen, already known for flouting literary conventions, ushered in a new era of vanity publishing with the limited-edition SUMO (1999). The size and scale of the 464-page tome meant it came with a bookstand designed by Philippe Starck to support its 34.8 kg heft.

Newton once told his friend José Alvarez, “I think that a photographer, like a well-behaved child, should be seen and not heard ... I am a photographer of the old school and have nothing to do with art ... I shall never indulge in intellectual talk about my work.” Yet Newton revelled in the attention his practice received and could be disarmingly candid. “When I take pictures, I don’t do it just for myself, to put them away in a drawer. I want as man y people as possible to see them.”

HELMUT Newton: In Focus is showing at the Jewish Museum of Australia: Gandel Centre of Judaica, Melbourne until January 29, 2023.

jewishmuseum.com.au

photo.org.au

Helmut Newton Foundation, Berlin

helmut-newton-foundation.org/en

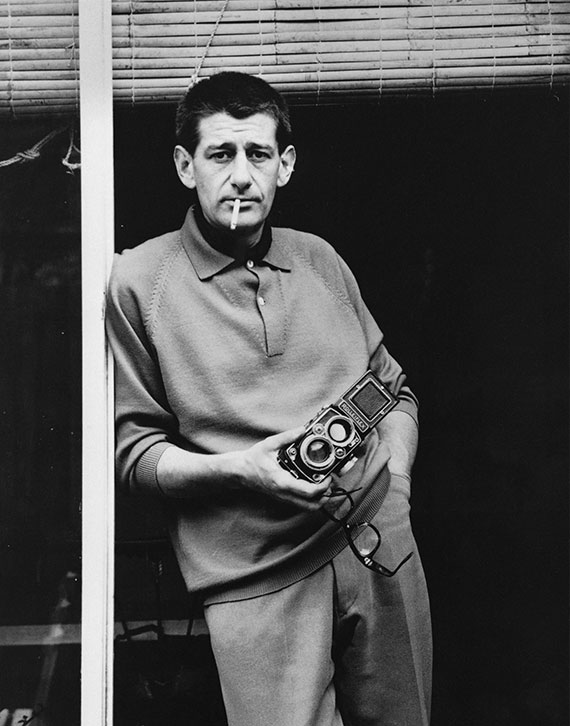

Image credit: Alice Springs, Helmut Newton, Melbourne, 1958, Copyright Helmut Newton Estate, Courtesy Helmut Newton Foundation

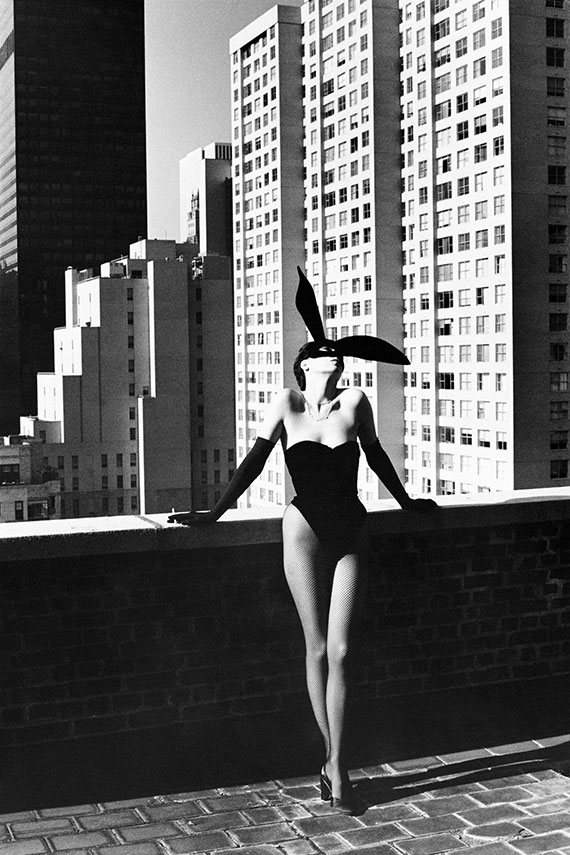

Image credit: Helmut Newton, Elsa Peretti, New York, 1975, Copyright Helmut Newton Estate, Courtesy Helmut Newton Foundation

Image credit: Helmut Newton, Shoe, Monte Carlo 1983, Copyright Helmut Newton Estate, Courtesy Helmut Newton Foundation

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 38 (May – Jul).

Click here to Subscribe