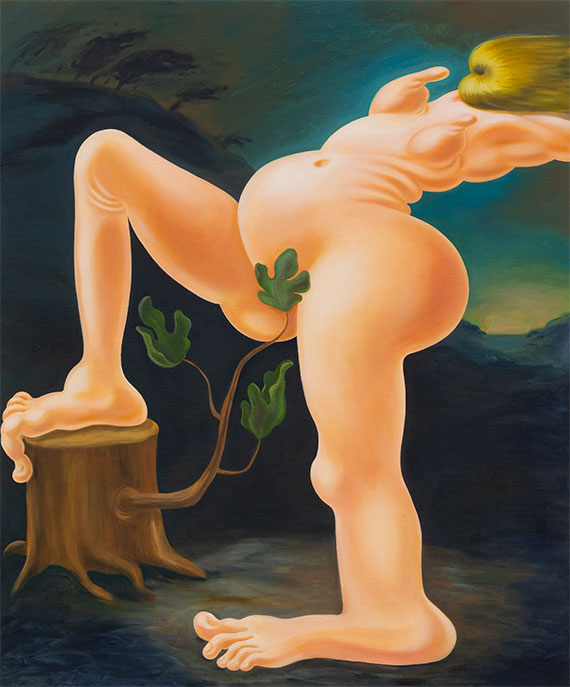

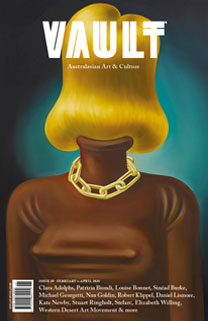

Louise Bonnet:

Grotesque Beauty

Louise Bonnet makes paintings that explore what it truly means to be human in all its awkward, visceral reality.

Image credit: Louise Bonnet, The Wind, 2019, oil on canvas, 152.4 x 182.9 cm. Courtesy the artist and Nino Mier Gallery, Cologne and Los Angeles

Swiss-born, Los Angeles-based figurative painter Louise Bonnet has cool cachet in spades and a résumé to match. Bonnet moved to LA after graduating from art school, but her rise to contemporary ‘It’ artist, with a waitlist of art collectors, was a bumpy transition.

Bonnet first worked as a graphic designer for brands XLarge and X-girl, the ultra-cool Kim Gordon streetwear brand, which is where she met her husband, ceramicist Adam Silverman. Surprisingly, he fired her from that role – but she says her heart wasn’t into designing endless street looks. In 2008 street artist Shepard Fairey, a friend from her designing days, gave Bonnet her first exhibition at his Echo Park gallery Subliminal Projects. Those acrylic-on-paper drawings were drawn from the familiar Hollywood lexicon of characters from The Shining, The Graduate and Carrie, among others.

They set the tone for her subsequent work with their spatial flatness; when Bonnet moved from acrylic to oil her work shifted in subject and style again. She has developed her own recognisable aesthetic language, which might be described as George Condo meets Robert Crumb meets Philip Guston – but with a distinctly feminist twist, uniquely her own. Bonnet’s ‘figures’ are a monstrous hybrid; they toy with the ‘monstrous feminine’. They are inhumanly human – all distended hands, bulbous shapes and awkward bulges. What informs this deformation? What is this tension between the beautiful and the ugly?

“I am not really overly concerned whether the figures are beautiful or ugly. I never think about it,” says Bonnet. “I always remember this quote from someone, I can’t remember who, that said: ‘I am not interested in art that wants to be friends with me.’ The figures are more an amalgam of feelings rather than actual people; it’s just I am more comfortable expressing it through the ‘human’ form. The shapes and bulges for me enhance a sensation of being out of control, or of trying to keep everything contained but things getting out of hand anyway, of being betrayed by your body and all the stuff you can’t keep tucked in. I like the edge of the precipice, or something just before it explodes, when all the energy is condensed and frozen for a second.”

Bonnet delights in grotesque banality. A recurring motif in her work is hair in abundant shiny swathes, slavishly painted. Bonnet explains, “I love hair. It’s so weird and so useless but we all spend so much time on it, worrying about it. I’m interested in all the things we do to try to hide the fact that we are apes. So, spending all this money and doing all these things to this fur on top of our heads – me included, don’t get me wrong – it’s fantastic.”

The hair, with its allusions to the abject, acts as a veil to obscure the faces of her subjects, ridding them of their personalities; these are portraits in absence of a subject. The hair might actually be the subject.

“It's true, I may be into this whole hair situation more than the face or eyes,” she says. “They take too much emotional space: if you put a face and eyes there, it sucks all the attention. I am not interested in having a dialogue with the figure. It’s there for you to look at, observe. They’re not supposed to see you. Maybe it’s voyeurism.”

She acknowledges, too, that this obsession with hair – its removal and management – is often viewed as a uniquely female preoccupation, and yet her work does not pass judgement either way. The figures themselves are at times androgynous, they may be men or they may be women – or they may be in a process of change. “Since they’re more of a bundle of feelings and thoughts rather than people, it doesn’t matter what sex the figures are. Even the ones with breasts don’t have to be female; it’s more about what breasts do to your shirt or your environment, or what’s done to them.”

An overly didactic reading of Bonnet’s work would suggest it might be a reaction to Instagram culture and its obsession with the body perfected, or a response to the plasticity of life in La La Land, but this would be reductive. Seen through the lens of 2019’s mainstream awakening, which saw the addition of the nonbinary identification term ‘they’ to the vernacular lexicon as well as official dictionaries, Bonnet’s work takes on a different purpose. This is not to say Bonnet is jumping on some kind of woke bandwagon. Her work is much smarter than that; she has always been exploring the tension between what a thing is and what is not.

When I look at Bonnet’s paintings; I notice that they relish the absurdity of the human condition, and the awkwardness of hiding the visceral reality of our bodily fluids, growths and imperfections. They remind me, too, of my own horrific and hilarious negotiations with my new body after having my first child: the awkward leaking, the soft doughy skin and flabby tone. What had I become?

Bonnet’s fleshy figures share a Boschian sensibility. I suggest the paintings are almost religious in tone, that they read like contemporary parables, or fables for a new generation. Bonnet agrees. “In the same way, the Renaissance portrait painters started to paint simple humans with the same care they were painting religious subjects before. It really gives them weight and importance.” This gravitas is key to her works’ solidity. They become less monstrous with each viewing.

Even though Bonnet’s subjects border on the ludicrous, her painting technique is quite the opposite. It is almost reverential, and she takes great care in the rendering of her subjects. Bonnet says, “I think a lot of my work is pretty funny but I do take it very seriously. I used to look at a lot of medieval Flemish painting; a lot of it is religious painting, and the way it’s made really conveys the importance and gravity of the subject, really carries it. I really respond to that. It’s funny but it’s not a joke, if that makes sense? It takes a long time to make them so I have time to really try to resolve the idea.”

Her recent work, I suggest, is more pared back, ‘less is more’ in approach. “That’s true. I add stuff when I get scared because I think that it’ll distract you from the fact that it sucks. So now I try to stop that and remove things and hope it’s good enough to stand on its own.”

Nino Mier Gallery in West Hollywood is currently exhibiting a selection of seven oil paintings by Louise Bonnet in her third solo show with the gallery. All the works were completed one year into pandemic-induced quarantine and are inspired in part by Agnès Varda’s iconic film ‘Vagabond’ (1985).

Vagabond by Louise Bonnet will continue until June 19, 2021.

miergallery.com/exhibitions/louise-bonnet3

Bonnet is represented by Nino Meir Gallery, Cologne and Los Angeles, Gagosian, Basel and New York, and Max Hetzler Gallery, Berlin.

maxhetzler.com

miergallery.com

gagosian.com

Image credit: Louise Bonnet, The Satin Sheet, 2018, oil on linen, 101.6 x 76.2 cm. Courtesy the artist and Nino Mier Gallery, Cologne and Los Angeles

Image credit: Louise Bonnet, Cleopatra, 2019, oil on linen, 182.9 x 243.8 cm. Courtesy the artist and Nino Mier Gallery, Cologne and Los Angeles

Image credit: Louise Bonnet, Untitled - Lighted Handshake, 2019, oil on linen 152.4 x 182.9 cm. Courtesy the artist and Nino Mier Gallery, Cologne and Los Angeles

This article was originally published in

VAULT Magazine Issue 29 (February – April 2020).

... Subscribe