Art Outsiders: Outside Voices

Over the last few years, the art world has become increasingly fascinated with self-taught artists, mystics and visionaries. But when viewing outsider art through the lens of ‘otherness’, we risk undermining the power of the work itself, writes Neha Kale.

Image credit: Madge Gill at Work, 1947

There are few 21st-century artists who epitomise the ways in which making art can be a form of survival quite like Henry Darger. As a child the artist, whose mother died when he was four, was sent to the Illinois Asylum for Feeble-Minded Children, a place known for brutal violence. Later, he moved into a sparse one-room apartment in Chicago’s down-and-out Lincoln Park neighbourhood. He spent his days mopping floors and rolling bandages as a hospital janitor. But he spent his nights working on a 15,000-page manuscript illustrated by hundreds of paintings and collages. These works depict The Realms of the Unreal, a parallel universe in which adult male soldiers waged a vicious and bloody war against angel-faced young girls with penises. They’re disturbing, yes. Darger has alternately been labelled a madman, a psychopath and, according to one 2005 Guardian article, a serial killer; his output, as Olivia Laing puts it in her 2016 book The Lonely City, is “a lightning rod for other people’s fears and fantasies about isolation.”

But his work is also intricate and impossibly beautiful. To stand in front of it is to be confronted with all the horror and hope and abject pain of living, rendered in intricate lines and delicate watercolour. (Darger famously scrounged the streets for art supplies, painstakingly tracing his figures from magazines and children’s books.) In many ways, Darger’s artistry has become intertwined with a larger mythology – that of the reclusive genius who worked outside culture and history, sublimating his deepest fears and desires via ink and paint.

Since his death, Darger has emerged as the patron saint of Outsider Art, the 1972 term coined by critic Roger Cardinal to describe art produced by those on the margins of society. It has roots in art brut, the French artist Jean Dubuffet’s 1940s definition of art produced by “people untouched by artistic culture […] derived from their own resources and not from the conventions of classic art or the art that happens to be fashionable.” The Chicago artist’s work was a fixture of January’s Outsider Art Fair at New York’s Metropolitan Pavilion. He’s also far from alone. As the art world increasingly lurches towards globalisation and the attendant threat of aesthetic sameness, it’s also – ironically enough – become hungrier for singular work by marginalised artists who lived and worked outside the system. There’s Bill Traylor, a former slave from Alabama whose freewheeling drawings, made on found cardboard, were the subject of an October 2018 retrospective at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington. There’s Madge Gill, a British nurse who made ornate, hallucinatory etchings under the apparent influence of a spirit guide called Myrninerest, whose works are currently on display at London’s William Morris Gallery. And there’s Purvis Young, the homeless former prisoner whose frenzied paintings of urban life materialised in the alleys of Miami’s Overton neighbourhood in the 1970s and who made his posthumous debut at this year’s Venice Biennale.

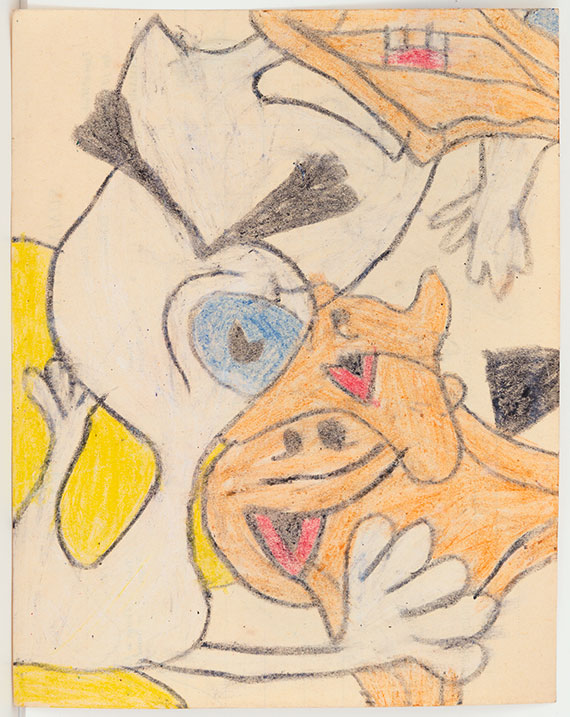

Closer to home, MONA’s 2017 presentation of James Brett’s Museum of Everything introduced Australian audiences to the likes of Terry Williams, the Melbourne artist whose soft sculptures, made of fabric scraps sutured together, blur the line between the human and the alien. It also showed Stan Hopewell, the Perth electrician who devoted himself to painting celestial abstractions after his wife Joyce became terminally ill. And after decades of obscurity outside her native New Zealand, Susan Te Kahurangi King, an Auckland-born artist with autism spectrum disorder whose Technicolor pictures, peopled by a sugary-yet-sinister parade of cartoon ducks and human figures, is – thanks to a new retrospective at Chicago’s Intuit: The Centre for Intuitive and Outsider Art – finally garnering the global acclaim she deserves.

It’s difficult to argue that the growing recognition of outsider artists is anything but a positive development. There’s something compelling about artists who’ve managed to evade the performative trappings of the modern art world (Art fairs! Instagram!) and cleaved to an original vision. More importantly, acknowledging the voices of marginalised artists is part of the larger project of remaking the canon – an art-world imperative that’s grown more urgent as the real world descends into populist politics and the threat of ecological crisis.

But even as so-called Outsider artists become more visible and marketable (in January 2018, Christie’s valued a Darger work at USD$400,000), their work is still too often overshadowed by biography and lumbered by the weight of difference, relegated to satellite fairs and standalone presentations rather than major collections. As critic Jerry Saltz put it in a 2013 response in Vulture to New York’s Outsider Art Fair, “MoMA and other museums once drew strict lines between insider and outsider because they were beset by accusations that modern art could be made by disturbed people and untrained artists.”

This implicitly positions work by Outsider artists as accidents of otherness rather than products of finely tuned visual intelligence and lifelong creative labour. It ignores the ways in which art history has traditionally privileged certain kinds of subjectivities. Worse still, it fails to recognise the ways in which notions of aesthetic value have always been shaped by access and privilege, often rooted as much in an artist’s proximity to power as in their skill or artistry.

But as Christine Smallwood puts it in a June 2015 New York Times article, “work that is made by someone who may not have had language, or for whom patronage, gallery representation or fellowships are non-concepts, is work that behaves differently.” Outsider art is easy to mythologise. But, if we let it, it can free us from our ideological blind spots. It asks us to question our own aesthetic criteria. What is ‘good’ art? What is ‘bad’ art? How can we tell them apart?

And, ultimately, it can make us more generous and empathetic viewers – for whom King’s difference is less interesting than the ferocity of her imagination, Gill’s eccentricity comes second to her astounding technical ability and we read Darger’s work, not in terms of the tragedy of his life, but in light of the rigour of a visual universe that expands and explodes our understanding of what art can be.

Image credit: Susan Te Kahurangi King, Untitled, 1958-59, crayon on paper, 19.05 x 14.6 cm. Photo: Adam Reich. Courtesy the artist and the American Folk Art Museum Susan Te Kahurangi King Fellowship

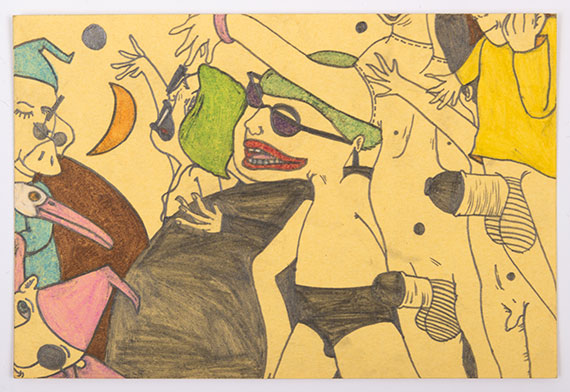

Image credit: Susan Te Kahurangi King, Untitled, 1967-70 graphite and coloured pencil on paper, 10.5 x 15.5 cm. Courtesy the artist, Chris Byrne and Andrew Edlin Gallery

Image credit: Madge Gill, Sans titre, carton (Chinese ink and coloured pencil on cardboard), 17.8 x 23 cm. Photo: Amélie Blanc. Courtesy Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Image credit: Madge Gill, Untitled, black ink on card

Image credit: Intuit, The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art. Photo: Cheri Eisenberg

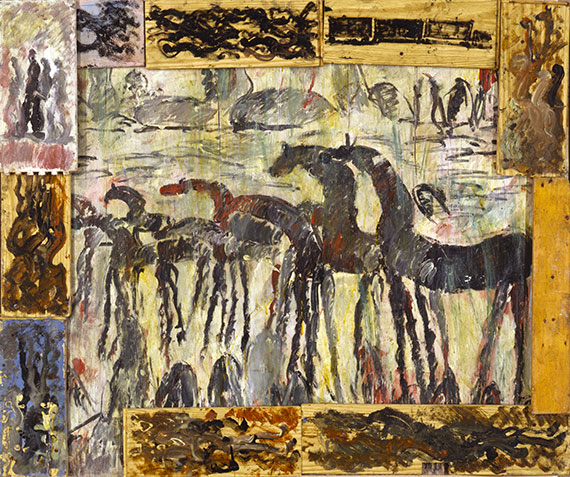

Image credit: Purvis Young, Untitled, 1988, acrylic on plywood with fiberboard Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase, 1994.25 © 1987, Purvis Young

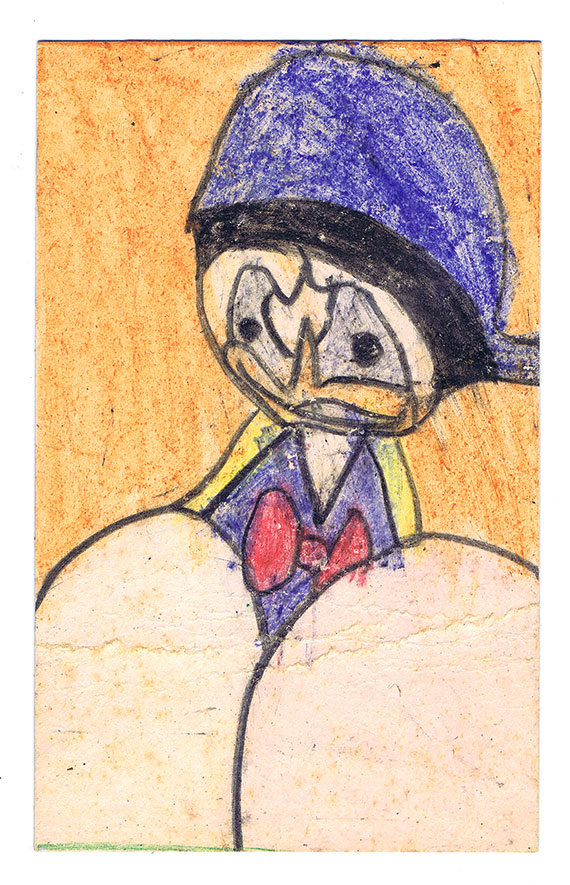

Image credit: Susan Te Kahurangi King, Untitled, 1958-59, crayon on board, 20 x 13 cm. Courtesy of the artist and the American Folk Art Museum Susan Te Kahurangi King Fellowship

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 27.

Click here to Subscribe