Nuance & Negligence: What do We do When Morality and Art Collide?

How do we address the contentious artworks of history? How should we talk about these artworks in a post #MeToo context? Bri Lee asks the hard questions.

Image credit: Alice Lang, Slutz Vote, 2017, marbled paper and acrylic on paper, 48 x 61 cm. Courtesy the artist

The #MeToo movement crashing into the art world has left us with murkier matters than simple two-sided debates over aestheticism and censorship. The first casualty of call-out culture can often be nuance, but these reckonings – these truths coming to light – are also necessary and important. When our art reflects our society and culture back to us and that reflection is ugly, the challenge is what to do next.

It would seem that the art world has quickly acquired a firm backhand for non-artists whose behaviours come under scrutiny. Late 2017 saw a few giant pillars fall. Knight Landesman was a longtime publisher of Artforum magazine and also a power broker in the art world. He resigned after nine women filed a civil law-suit against him that contained allegations spanning almost a decade including “groping them, attempting to kiss them, sending them vulgar messages and, on occasion, retaliating against them when they spurned his advances”.

Landesman certainly isn’t alone. British gallerist and art collector Anthony d’Offay has stepped down as curator of Artists Rooms, famous art collector Steve Wynn resigned as CEO of his casino company, Benjamin Genocchio was “ousted” from his role at the Armory Show, and Los Angeles art dealer Aaron Bondaroff, who co-owns the Moran Bondaroff Gallery, resigned also. What do they all have in common? Their job losses occurred soon after serious accusations of sexual harassment and/or sexual assault were made, but before any alleged offending was ‘proven’ in the traditional legal sense. These men would still be working if not for the #MeToo movement. But what do we do with actual artists? The loveable rascals! Those beacons of wayward genius we beg to make legend. Their boundary-pushing, their addictions and predilections, their fearlessness in the face of convention and decorum... can we turn around and slap them too?

Chuck Close is one of the biggest names to have received the harshest smacks. Close is award-winning; his paintings and photographs hang in institutions around the world and his works sell at auction for multi-million-dollar sums. In December 2017 this critical regard was challenged when two women accused him of sexual misconduct after he invited them (separately) to his studio. HuffPost reported the account of one woman, the artist Julia Fox: “he then moved toward her in his wheelchair ‘so that his head was inches away from her vagina,’ and said it ‘looks delicious’.” Close denied making such comments but acknowledged (in The New York Times) that he has spoken to women candidly and even crudely about their body parts. “I acknowledge having a dirty mouth, but we’re all adults,” he said in a statement labelled an “apology”.

The following month the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC announced the cancellation of his show (scheduled to open that May) due to the allegations. There was uproar on both sides. Fresh blood was celebrated by some and cries of “censorship” filled the op-eds of others.

In contrast to that polarising madness, The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia chose to continue its show of Close’s photographs that were on display during that month The New York Times published the controversial story, but went a step further. They spoke with the community, they held a forum, and they listened. The result was an interactive pop-up exhibition and project space near Close’s exhibition dedicated to an interrogation of issues of gender and power. The museum’s director, Brooke Davis, told The Art Newspaper that cancelling the show would have projected a false sense of having dealt adequately with the issue, saying “I felt that the conversation was more important than having a sense of victory.”

Worth noting is that both institutions acted as though they believed the accusations levelled at Close. This alone is enough to make many people uncomfortable. Of course, #MeToo was never about comfort, rather about preventing the widespread discomfort so many women are currently and relentlessly exposed to. However, while accusations are not yet ‘proven’ in court, countless other institutions with Close’s works currently on display did nothing.

In June this year Rozanna Lilley, the daughter of famous Australian playwright Dorothy Hewett, published her book of poems and personal essays titled Do Oysters Get Bored? and spoke in multiple interviews about the abuse she and her sister Kate suffered at the hands of artists who visited the family home in the 1970s. The scene set is one of bohemian excess with a sideline of sex crimes; Hewett encouraged her artist friends to make sexual use of her daughters. British photographer David Hamilton (who killed himself in 2016 after allegations of rape were made against him), artist Martin Sharp, and the playwright and speechwriter Bob Ellis all featured. About these anointed artists Lilley told The Saturday Paper: “Many of them think they’re geniuses, and many others think of them as geniuses. And the basic attitude is that you’d be lucky to have anything to do with them. You’d be lucky to have sex with them. Like they’re doing you a favour. That’s a part of the artistic milieu then.” Lilley insists none of this story has been a secret, even though a shockwave undeniably went through the Australian artistic community when the story came out in The Weekend Australian. The world after #MeToo seems to have less and less patience for the boundary-pushing, lovable-rascal narrative.

The most common justification for inaction (other than “nothing has been proven yet”) is aestheticism – the idea that the value of the art can (and should) be separated from the life of the artist. Many directors claim it is not their role to make “moral judgments” about the lives of the artists whose works they display. The trouble with this argument is that their institutions make money from the popularity, scandal, hate, and love of the lives of the artists they display. It is naïve (borderline absurd) to think that the works on the walls of public-facing (and in Australia, often publicly funded) galleries are chosen for their aestheticism alone. Who on earth would argue that Keith Richards’ lifestyle and legend had nothing to do with the success of the Rolling Stones? Our treatment of art stars is the same; they are idols and celebrities and icons, and audiences gather to see the work they make. Galleries print large, expensive exhibition-catalogues-cum-biographical-compendiums of the works and lives of the artists they display in major exhibitions, and they sell these books in stores attached to exhibition spaces. While institutions benefit from the behaviours and profiles of the artists, they cannot then simultaneously simply reject them on grounds of aestheticism.

But then again, what about long-dead artists whose actions simply no longer stack up? The ‘floodgates’ argument is another popular refrain of those afraid of the #MeToo movement affecting the art world; that if we removed all the artworks by men who treated women badly by today’s standards there would be bare walls and significant portions of art history missing. Picasso, who allegedly abused some of his lovers, once described women as “machines for suffering”. How do we judge him in 2018?

In the Australian legal system we do not retrospectively punish, either by making things illegal looking backwards or by increasing the sentence passed today for an offence committed several years past. In taking this stance the law is telling the world: you are to be judged by the attitudes of your peers at your point in time. Where does this leave an artist accused of misconduct, say, 10 years ago? We seem to be okay with Picasso because it was “different then” but are we okay with behaviour that causes lasting damage to someone’s life and career, but that was perhaps less obviously bad in, say, 2008? The complexity is that we are looking back in time through the #MeToo lens and judging it abhorrent. Something about this is inherently unfair. On the other, basic human rights aren’t a mystery. The simplicity of expecting people to go about their lives without hurting others cannot be overstated.

Let’s take an easily polarising example. We may talk about it more now, but it has been a long time (i.e. ancient Greece) since we thought it was acceptable for adults to behave sexually towards children.

How, then, does a self-professed child sex offender have works on display across major Australian galleries and libraries, with no word of warning or context provided the average visitor? Aestheticism is one answer given. In an ABC News report calling attention to Donald Friend’s portrait hanging in the Tweed Gallery, director Susi Muddiman said, “Fundamentally it is not the gallery’s role to make a moral judgement on the work of artists,” and also cited the fact that other institutions around the country elevated and displayed his works. The public felt differently. Shortly after the ABC article was published the portrait was removed and “the official line differs as to the reason”. So then a new question has arisen: is it the sole discretion of a director of a gallery to choose which moral questions to address or answer? And does it make a difference if that gallery is publicly funded?

Artworks have narratives that can – and should – change over time, even posthumously. An exciting dialogue can occur when given the space. The recent Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales featured his controversial photography series depicting nude African-American men, but also included cards and walls with information about why it is considered racial fetishism and morally questionable. Art chosen to hang in a major national gallery is inherently celebrated and affirmed, but that does not mean it cannot also be questioned and contextualised.

This is sometimes referred to as ‘the asterisk’ approach. The work is not censored. The artist is not struck from the record. The art world doesn’t get to feel like it’s solving a social problem by no longer facing its ugly reflection.

So it would seem there are three options for the art world to choose from when #MeToo meets an artist. Complaints of misconduct can be ignored or denied, but only for so long, until the public come knocking demanding action. Works can be removed from display, but then the problems they represent are also hidden from sight, and the progression of art history through society and time is lost, and we do risk verging upon censorship in certain circumstances. The third option is the hardest and requires the most patience and nuance: engage. What text needs to sit under that asterisk, and who should write it? How can we elevate silenced voices in gallery spaces so that the inequalities that allowed these instances of misconduct to happen are not allowed to fester, implicitly encouraged?

Then, at the end of the day, the question becomes simple again: what kind of art world do we want to live and work in?

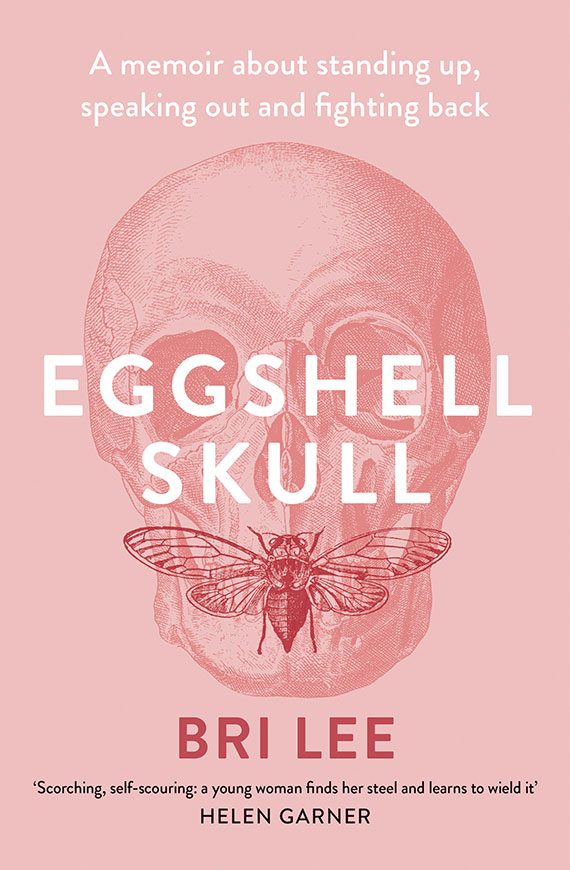

Bri Lee is a writer and editor. Her first book, a memoir, Eggshell Skull was published in May 2018. In 2016 Bri was the recipient of the inaugural Kat Muscat Fellowship, and in 2017 was one of Griffith Review’s Queensland writing fellows. She is the founding editor of the quarterly print periodical Hot Chicks with Big Brains. In 2018 Bri received a Commonwealth Government scholarship and stipend to work on her second book at the University of Queensland. She is qualified to practise law, but doesn’t.

Alice Lang is an Australian artist currently based in Los Angeles. Her cross-disciplinary art practice utilizes ceramics and painting to examine how existing power structures disseminate and manifest within individual bodies and mass culture. Her work examines how the shifting cultural and contextual relationships between text, objects and images can subvert dominant paradigms and reclaim space for female voices.

Lang graduated from the MFA program at CalArts in 2015 and has completed residencies in Canada, New York and Los Angeles. She has received awards such as the Queensland Art Gallery Melville Haysom Scholarship (2009), Australia Council New Work Grant (2012), Lord Mayor’s Emerging Artist Fellowship (2012) and the Freedman Foundation Traveling Scholarship for Emerging Artists (2013). She is also a founding member of the feminist art collective LEVEL which is based in Brisbane, Australia.

Image credit: Alice Lang, Alice Lang Originals, 2015-ongoing, doll porcelain cast from 3D body scan of the artist, 13 x 9 x 14 cm. Courtesy the artist

Image credit: Eggshell Skull (2018) by Bri Lee Published by Allen & Unwin

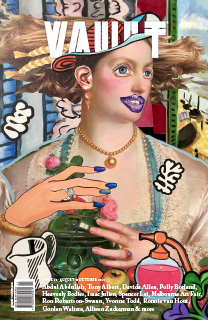

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 23.

Click here to Subscribe